International climate finance / Pledges & Commitments / Transparency

Before the G7 summit: Developed countries climate finance projections fail to deliver clarity and predictability

At the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in 2015, in Paris, developed countries committed to support climate efforts in developing countries by providing and mobilising at least $100 billion annually from 2020 onwards. This funding was an integral component of the global deal on climate, and failure to deliver on this promise will both undermine the implementation of the Paris Agreement and complicate future global climate negotiations.

Article 9.5 of the Paris Agreement obliges to report on future finance

Under the Paris agreement’s Article 9.5, developed countries are obliged to submit information on their planned future climate finances to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The first set of these submissions were due at the end of 2020. 23 developed countries who maintain an obligation to do so, plus the European Union, have so far provided them. As developed countries resisted to communicate their climate finance plans through the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), these Art. 9.5. reports need to be viewed as main channel for developing countries to learn which climate finance might be provided in the years to come.

Main findings of a new report reviewing the Article 9.5. country submissions

CARE has analysed these reports in its new publication “Hollow Commitments”, and the overall picture is very clear: rich countries are not providing evidence that they will meet the promised $100 billion target from 2020 onwards. One might expect rich countries to act when more than $20 billion still needs to be found annually if they are to realise their commitments. An appropriate response would be to ensure that their recently submitted reports showed precisely how much each country would increase their own climate finance to secure their common goal. Yet only three countries, Luxembourg, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, put forward numbers demonstrating a planned increase in their climate finance across multiple years. As a result, the information provided by rich countries suggests that international climate finance will increase by just $1.6 billion in 2021 and 2022, compared to the amount provided in 2019. An additional five countries indicate their finances will largely remain constant in coming years, while most of the countries provided almost no quantitative information regarding indicative future levels of support, despite this being the main purpose of the reporting. Furthermore, no countries provided information on what they considered to be their fair share of the $100 billion, how such a number had been established, and how and when they would deliver on it. Indicative figures and plans highlighting future climate finance are not only important to ensure that rich countries deliver on their collective obligations. This information is also vital for developing countries, as it makes it possible for them to plan for and undertake adaptation, mitigation, and resilience building actions. One cannot call on developing countries to spend significant, and often scarce, resources of their own on planning actions, when the prospect of financial commitments in support of them remains uncertain. The 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, committed to by all developed countries, created a set of fundamental guidelines to ensure successful development cooperation. The Declaration underlined that predictability and commitments across multiple years are key determinants of effective support. The need for predictability in climate finance was also stressed in the decisions resulting from COP24, in 2018, which sought to clarify which information rich countries should provide in their future climate finance plans.

What’s in Germany’s Art. 9.5 report?

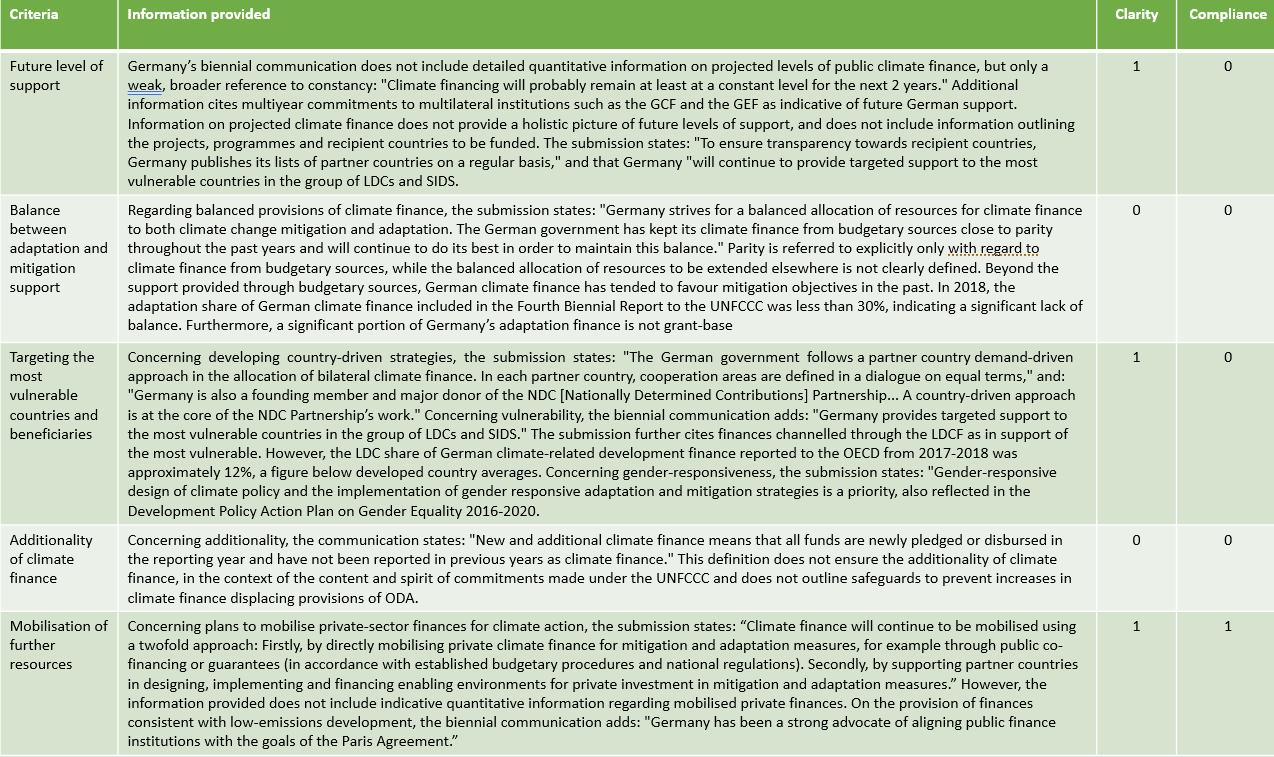

Germany’s Art. 9.5 report (contained with the overall EU report) has not been ranked in the top group, but only achieved 4 out of 10 possible points, putting Germany in a group of several countries ranked on 7th place.

Germany’s biennial communication makes little effort to ensure the predictability of its future climate finance for developing countries. The submission provides no enhanced quantitative information to outline future provisions of climate relevant finance, referring only to existing multi-year commitments to multilateral institutions. Germany has therefore not provided any information to indicate that its future provisions of climate finance will represent a progression beyond previous efforts. The communication provides no clarity explaining what is considered as a balanced allocation of resources for adaptation and mitigation objectives. Concerning the projects, programmes and recipient countries to be financed, sufficient detail to enhance predictability is lacking. The submission states that engagements with Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) will continue to be a high priority to the German government, but without offering any enhanced information regarding their support to such recipients in the future. Finally, the submission does not further define additionality in line with the content and spirit of commitments made under the UNFCCC. As Germany is one of the largest global providers of both ODA and climate finance, a lack of clarity regarding additionality could severely reduce the predictability of climate support in developing countries.

Table: Detailed assessment of Germany’s report under Article 9.5

Key recommendations

Based on the findings, the report draws the following recommendations:

- Ahead of COP26 in November 2021, developed countries should develop a clear roadmap and effort sharing agreement outlining each countries’ fair share of the $100 billion financial pledge which ensures that they collectively live up to their climate finance commitments. This should include how to achieve a balance between support for adaptation and mitigation, with at least 50% of finance going to adaptation, by no later than 2023.

- All countries, particularly large donors such as the G7 nations, should aim to at least double their public climate finance by 2025.

- Each developed country should redouble their efforts to plan their future climate support to ensure both predictability and a prioritization of the most vulnerable countries and people.

- The climate finance provided by developed countries should be new and additional to their commitments of official development assistance (ODA).

- When submitting their next biennial communications on projected climate finances by the end of 2022, developed countries should ensure that they do their utmost to honour the decisions of COP24 and fully provide the requested information.

For Germany specifically, the upcoming G7 summit from 11-13 June is an opportunity to communicate to the international community a high-level commitment to significantly increase climate finance in the next few years in particular for adaptation, to fill a gap the official report has been unable to fill. There is broad consensus among German civil society that a further doubling of German climate finance – to annually 8bn Euro of budget finance by 2025 – would be an appropriate German signal to contribute to the urgently required scaling-up of climate action in developing countries.

Sven Harmeling, CARE

Read full report: Hollow Commitments by CARE